Characteristics of the Sport

The length of play is not predetermined in tennis matches, so they can last several hours, involving high aerobic and anaerobic demands with repetitive stresses due to a variety of strokes and movements. There are hundreds of strokes per match.

Players use the whole body to generate high racquet and ball velocities, especially in overhead movements for power shots such as serves and smashes. This is called the kinetic chain, which begins with feet, knees, and hips, progressing with core and trunk, shoulder and elbow, and finally to the wrist, hand, and racquet.

Tennis can be played on different surfaces. Clay is considered to be a slower surface due to an increased shock absorption and loss of ball speed. Sliding becomes an integral part of playing on clay. Hard court has the highest coefficient of friction and lowest shock absorption, sliding is much more difficult, leading to shorter stopping distances.

Sports Medicine and Arthroscopic Surgery,

Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena, Madrid

Fellow MD, ISMEC

Sports Medicine and Arthroscopic Surgery,

Medical Director of ISMEC

Epidemiology of Injuries

The injury rate in tennis players has increased in the last 20 years. Recent data from ATP/WTA tournaments showed that women leave tournaments significantly more frequently than men (incidence rate per 1000 match exposure 65.65 vs. 52.68).

The most injured body section for both sexes was the lower limb being significantly higher rate for women (40.8%) than men (31.2%). When considering subcategories, the most injured anatomic part in women was the thigh with 10.7% (quadriceps and hamstrings), followed by the shoulder (8.9%). In men, low back injuries included 8.6% of all injuries followed by shoulder injuries (6.4%). Musculoskeletal injuries can occur in nearly all regions of the body, and most were defined as overuse injuries coming from repetitive microtrauma inherent in the sport.

Shoulder injuries accounted for the second cause of injury departures for both sexes, without relation to the type of surface, which indicates a general problem. It is believed that the imbalance in the eccentric-to-concentric ratio of the rotator cuff caused by the deceleration at the end of the serve/smash causes most of the shoulder injuries.

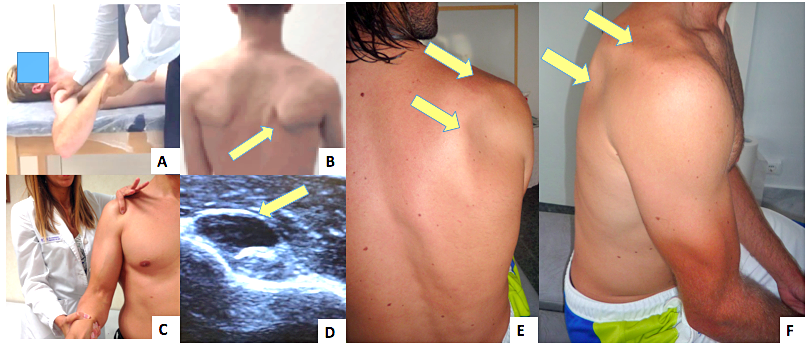

Focusing on shoulder injuries and adaptive changes, in the study with elite active tennis players by our group, players experienced GIRD (glenohumeral internal rotation deficit, 87.4%, Fig. A), dyskinesis (57.7%, Fig. B), long head of the biceps (LHB) tenderness (35.5%, Fig. C) and tenosynovitis on the LHB (20%, Fig. D) on the dominant shoulder.

Curiously, the mean external rotation (ER) was normal in both shoulders (93.8° on dominant and 93.3° on nondominant). Even if it seems that the nondominant shoulder might not suffer from these injuries/adaptive changes, it does; 56.3% had GIRD, 45.9% dyskinesis, 16.3% LHB tenderness, and 11.6% tenosynovitis on LHB on their contralateral shoulder.

Suprascapular nerve entrapment was also observed with a prevalence of 7.5%. In all of the cases, it appeared with atrophy of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus fossae of the dominant shoulder (Fig. E,F). and it was correlated to higher age and amount of hours played of tennis. Our theory is that this relates to a dynamic entrapment resulting from the altered biomechanics of the scapula and shoulder complex.

Injuries of the elbow region involve mainly lateral and medial epicondylitis. Lateral epicondylitis or “tennis elbow” rates in recreational players are quite high, mainly because of the overload on the backhand ground stroke, ranging from 37 to 57%, while the incidence of medial epicondylitis is higher in elite players caused by overload on the serve and forehand strokes.

Specific Rehabilitation and Return to Play

Conservative treatment will be effective in most tennis players. The developed rehabilitation methods are well researched and refined, and they should focus on the importance of scapular stability, dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint, proprioceptive work, and the techniques of reintroducing the specific movements.

The first step after injury is to control the symptoms, which can be achieved with ceasing or decreasing the aggravating activity; however, mobility must be maintained as much as possible. The most common incapacitating symptom of the upper extremity in tennis players is pain from the long head of the biceps (LHB), which prevents them from serving, as well as creating difficulty during the volley and forehand movement.

In case of severe pain, it may be advisable to inject triamcinolone and anesthetic under ultrasound control within the biceps sheath avoiding intratendinous injection. Other therapies can consist of radial shock, wave, platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections or percutaneous intratissue electrolysis with galvanic currents, all combined with

physiotherapy. Although not obligatory, this injection is useful as a diagnostic tool and also allows the tennis player to begin and tolerate the physiotherapy protocol sooner.

The suggested shoulder protocol starts focusing on improving scapular dyskinesis by working on the parascapular muscles to gain conscious control of the scapula. Then, shoulder extension, abduction exercises, and cross kinetic chain (the affected shoulder/scapula complex and the contralateral lower extremity) exercises are introduced. It is also very important to stretch the tight muscles inserting at the coracoid that might aggravate the scapular dyskinesis. The protocol progresses with strengthening exercises of the shoulder girdle including eccentric and isoinertial exercises to improve LHB tendinopathy. In order to improve GIRD due to posterior muscle tightness, the “sleeper” and towel selfstretching exercises are indicated.

Taking time to explain every exercise and correct the position as well as involving the tennis player team is essential to achieve good results. A comprehensive rehabilitation program takes into account the individual requirements of a tennis athlete as well as individual external, biological, and physiological factors that can influence a player’s rehabilitation.

Prevention Strategies

There is evidence that training may have a protective effect and that under training increases injury risk.

Multiple studies have identified alterations or changes in strength balance and muscle group performance in elite tennis players, which end up causing alterations in the kinetic chain and therefore injuries. Thus, commonly injured areas should be targeted for preventive training strategies. As tennis is an asymmetric sport, the prevention strategies should also focus on achieving the most symmetric muscle-joint status as possible by working in the gym to strengthen and stretch the nondominant sides such as the contralateral upper extremity or the ipsilateral core muscles.

The prevention strategies are focused on resistive exercises for core, shoulder, elbow, hip, and lower extremity.

The movements required in tennis include repeated flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation of the spine; therefore, extensive core stability training is critical to avoid back injuries and kinetic chain disorders. Most of the exercises explained in the rehabilitation program for shoulder injuries are also used in prevention programs.

Exercises recommended for the prevention of elbow and wrist injuries are based on increasing the strength and muscle endurance of the wrist and forearm muscles. There are other sports science disciplines, such as psychology, exercise physiology, and pedagogy/motor learning that could also make a case for their role in prevention strategies.

Another important step in prevention injuries is regular movement analysis of the players to pick up weaknesses or unhealthy movement patterns, which could lead to an overuse injury. These steps should be realized together with the coach, who can implement changes to the technique, as well as training exercises to help prevent injuries and assure a good physical condition of the athlete.